so I tried to answer the question “why” 3 times and I couldn’t quite figure out a good angle to attack it from so i ended up combining my thoughts in an essay that answers nothing and should probably not be posted on the internet! alas, that is what we do at Thoth: we pooblish foolish thoughts on the interweb and never ask why or tink about zee ramifications.

Prologue: Why? (should i b ok with life being unfair)

—-

“The day the music died.”

Don McLean delivers it perfectly, almost stumbling through the line.

“I can’t remember if I cried when I read about his widowed bride,” he states. “Something touched me deep inside,” he croons. “The day,” he pauses. “The music died,” he whispers.

—-

“The day the music died.”

At face value, it’s a lyric from American Pie referencing February 3, 1959.

A plane crash took the lives of three musicians that day: Richie Valens, The Big Bopper, and Buddy Holly. Buddy’s wife was pregnant and suffered a miscarriage shortly thereafter.

—-

“The day the music died.”

It’s a phrase that taught me a lot about the question “why?”

There is a line of demarcation embedded in the expression. Before the music died, life was one way. After the music died, life changed, and something important was lost. I hate and love this.

—-

“The day the music died.”

It feels like this is how life goes: bad things happening is not a plot twist.

To Don Mclean, to America, the day the music died was when three talented men were taken away for seemingly no reason. A tragedy without a story arc. That seems to happen a lot.

—-

“The day the music died.”

Nothing can really prepare someone for the day the music dies.

The words suggest that sometimes bad things will happen to good people. Even worse, the words promise that sometimes bad things will happen to good people and it will be random.

—-

“The day the music died.”

“The music” is referencing so much more than Buddy Holly.

Let’s move past the literal interpretation that “the music” is a reference to Mr. Holly. I don’t think that’s how the song is supposed to be heard. I’ve always preferred a different perspective.

—-

“The day the music died.”

“The music” dying is universal and personal.

Everyone’s “music” dies at some point or another. Sometimes it’s a literal death – of a friend or family member or partner. Other times it's a more abstract death – of a job or a passion or a friendship.

—-

“The day the music died.”

To me, “the music” is anything that I love and identify with.

My life has so far carried more than a few tunes, and I can look back point at a handful of days when my music died. I bet everyone can. It’s why the lyrics are so haunting. They stick.

—-

“The day the music died.”

And when the music dies, I always ask why.

But that’s the great thing about American Pie. The music dies, but the song doesn’t end, it just changes, continuing for seven more beautiful minutes of perfection. There’s probably a lesson there?

Interlude: Why? (am I here and what should i be doing)

—-

One of my favorite mental models for the “why” of life is an article I recently read about choosing good quests.

The moral of the story is that, at any one moment, we humans tend to make a single objective the center of our lives. Like, someone might have 100 things going on, but there is always that one thing that acts as the sun – it is central to who you are, what you are doing, and all that jazz.

For example, while I am juggling quite a few balls at the moment as a Thoth Writer, Catan Enthusiast, Brandon Sanderson Reader, Good Brother, and Single Dood, none of that stuff is my central quest. No, at the moment, those are all secondary quests to my weird passion for building open and decentralized payment rails – and every decision I make right now is dependent on whether this/that will affect me pursuing of that passion.

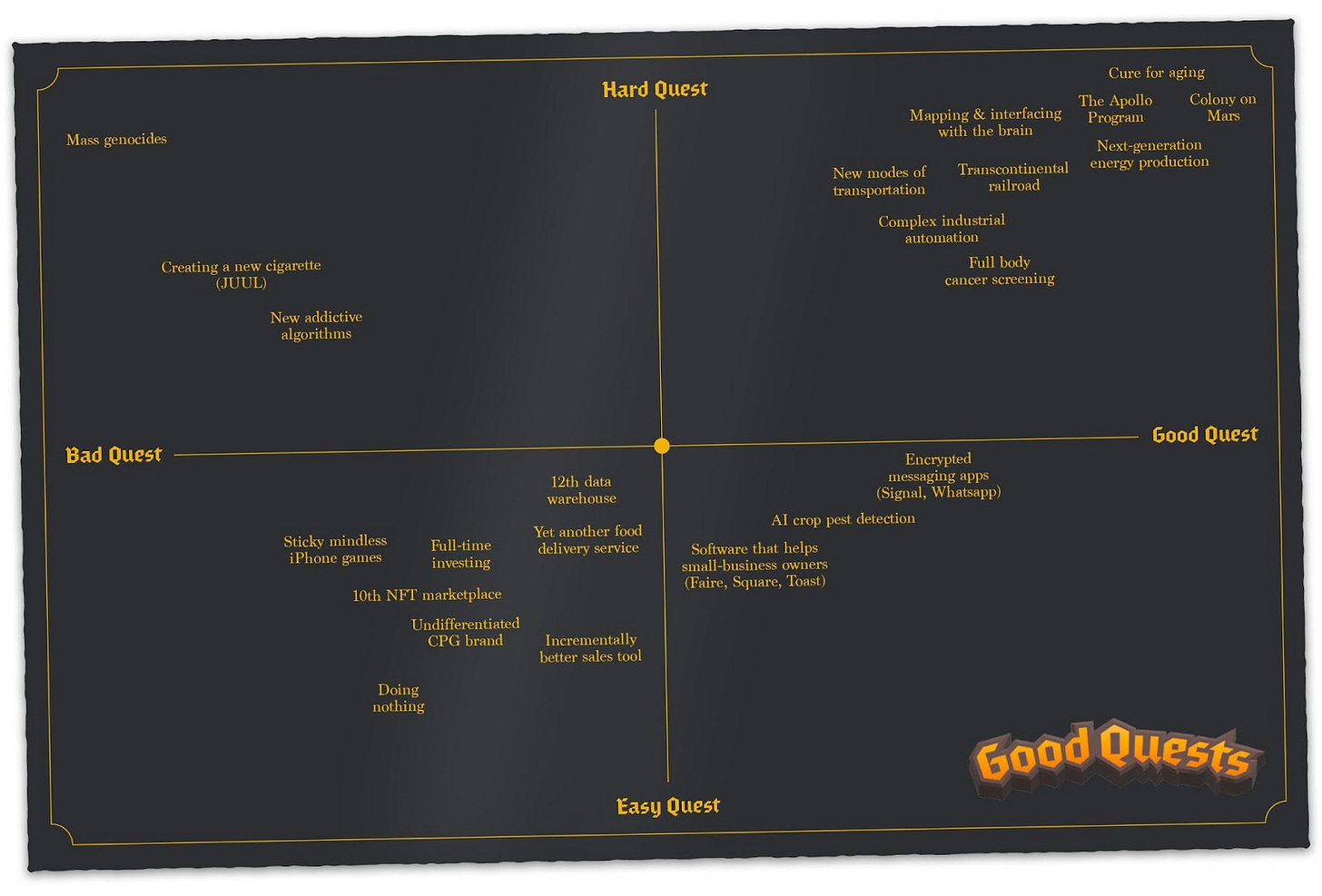

The article, which is literally called “Choose Good Quests” is all about, well, being able to determine if a quest is worth bending the rest of a life around it.

Quests tend to manifest as an objective we center our lives around. Your quest might be to reach a specific milestone: to become a senator, to publish a book, to make a million dollars. But not all quests have an end state. You might be on a quest to maximize your net worth, or to bench-press more weight than anyone else at the gym. Maybe you’re just on a quest to have the most fun possible before you die. A far cry from refrigeration or running water, but a nice life. As you’ve probably already intuited, not all quests are created equal.

In the most simple terms possible: a good quest makes the future better than our world today, while a bad quest doesn't improve the world much at all, or even makes it worse.

The article went on to even create a chart (i love charts) showing what good quests might be in terms career building.

I really, really like “good quests” as an answer to the question of “why” because it is open-ended.

The choosing good quests model allows my answer to “why” to change as life changes while still keeping me in check from taking on bad quests.

For example, my “good quest” right now does not need to be the same that 42-year-old Kram might be partaking in. The only thing that matters is that both 24 year old Kram and 42 year old Kram are making the central objective of life a good quest.

For now, it sort of makes sense that building something cool on the internet is my quest of choice. But in 20 years, it might make sense that building something cool on the internet is a waste of my talent, which could be better utilized as a teacher or dad or something.

—-

Arthur Dent, aboard the Heart of Gold, traversed galaxies and battled Vogons in Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy to learn that, simply put, the answer to the “Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything” is, um “42.”

In the book, “42” was calculated by a supercomputer named Deep Thought after a 7.5 million year experiment on an organic simulation called “Earth.”

It’s an amazingly silly answer in an amazingly silly book about the end of the world, Great Britain, and aliens, yet it has always stuck with me. The main character, Arthur, had gone to such great lengths to track down Deep Thought and get and answer that he thought would solve everything and give him purpose. Instead of a resolution, Arthur was given an arbitrary answer that, um, didn’t really leave him with a better theory for living life.

And, like, that’s super sad on the one hand because it feels like the universal question of “why” should not be solved by two numerals and it sorta seems like Arthur wasted quite a bit of time on a futile adventure. But, on the other hand, when you zoom out on the story, Arthur actually found some cool stuff along the way in his pursuit of ~the answer~. Ya know, he learned how to fly a spaceship, he made new friends (shoutout Zaphod Beeblebrox), and, of course, he figured out how to have fun after previously being trapped in a middle-class prison of tea and crumpets back in England.

While Arthur didn’t really find a good answer to “why” he did find out how to live life in a better way, or something like that.

I love that the answer to life might be 42 and that there is probably no satisfactory answer to the question of “why”. I’ve always been more about the journey than the destination anyways – it’s why I follow a passion and not a career and why I was obsessed with perfection rather than winning back when I was an athlete.

Epilogue: Why? (is quite an ethereal concept)

—-

There’s a poem that I really like that talks about thoughts as a distraction from infinite. Reading it made me think about how hard it is to find a satisfactory answer to “why”.

—-

Increasingly, I do things to distract me from my thoughts.

The distraction helps my thinking.

it complicates my thoughts—it adds a mood, like

background music.

It makes me interesting to myself.

I once heard someone say, That’s like drinking to remember,

but I like drinking to remember.

I like when bad things happen, but not the ones I was

expecting.

I like when something feels like a placeholder that never

got replaced.

I like the feeling of starting to like a thing I used to hate.

Like cheating on myself.

I like how you remember your hotel room number for the

length of your stay, and then it’s gone from your mind

forever.

I like to think about infinity, the curve that approaches the

asymptote

I like to think about the difference between hearing

someone lie and watching someone lie.

A difference of point of view—their point of view, not mine.

There are orders of infinity, infinite sets that are not only

larger but infinitely larger than the first order of infinity—

but you know all this.

I like thoughts before they coalesce into “thoughts.”

Before-thoughts.

I like when people lie a little bit and then admit it.

I like when there are buildings on the sides of mountains.

I like when there’s a hole in the roof of a building, to watch

clouds blow through.

- kram

Amazing . . . deep, thoughtful . . . how you connected all the dots blows me away, and I am in awe!

I have lived long and the music has died and rebounded in mysterious ways . . . while I may never know the answers to "why" as I watch lives unfold, I know God is in control and He is always good.

use of an exclamation mark in the intro = uh oh